The Roma Presence in Senné from 1930-1939

When examining the historical records of Senné, a small village in Slovakia’s Michalovce region, a fascinating — and sobering — piece of history emerges.

Through newly accessed scans from Slovakiana’s archives, we can confirm that Roma (Gypsy) families were officially documented in the 1930 Czechoslovak census, and even more critically, were separately categorized during administrative updates in 1939–1940.

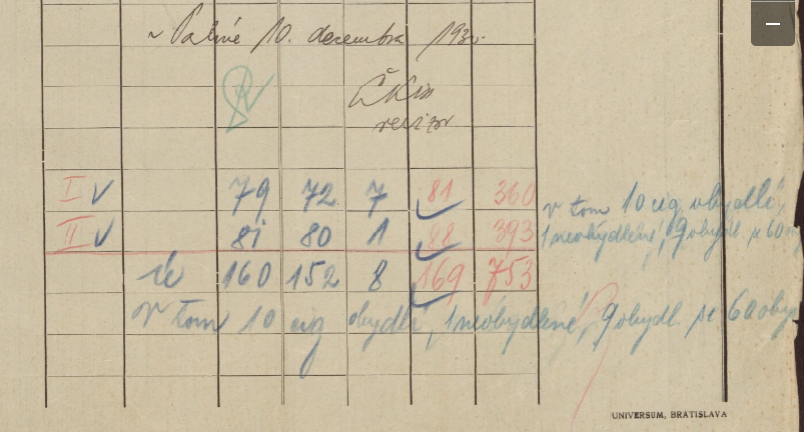

The first major page, the 1930 municipal overview sheet for Senné, shows detailed breakdowns of the village’s population by households and dwelling types.

Although initially recorded neutrally under the Czechoslovak Republic, later administrative marks, scrawled in blue and red pencil, reveal profound shifts. These annotations were added under the wartime Slovak State regime, which closely aligned with Nazi Germany.

A zoomed-in excerpt (shown below) from the bottom of the census summary clearly notes:

“v tom 10 cig. obydlené, 1 neobydlené, 9 obydlené po 60 dň.”

Translated, this states:

“Among these, 10 dwellings inhabited by Roma (Gypsies), 1 uninhabited, 9 inhabited for over 60 days.”

This simple line carries enormous historical weight.

By 1940, new Slovak policies — influenced by German racial ideology — began systematically categorizing Roma separately from the general population. What began here as a handwritten annotation would later escalate into restrictions on movement, forced relocations, labor camp internments, and tragic massacres during the later phases of World War II.

In the case of Senné, at least 10 Roma households were officially registered — a relatively significant number given the village’s small size at the time. The “60 days” residency note was legally significant because Slovak authorities often used short residency status as a justification for evicting or segregating Roma families.

These small administrative traces from the Senné 1930 census — defaced and updated by 1939 bureaucrats — provide a raw glimpse into the slow, bureaucratic buildup of ethnic targeting that would culminate in tragedy across Slovakia during the 1940s.

Why the Roma Notation in 1939–1940 Matters

| Category | Why It’s Significant |

|---|---|

| Ethnic Targeting | The Slovak State (1939–1945), under Nazi influence, began systematically tracking Roma for racial and security reasons — along with Jews and Hungarians. |

| First Steps Toward Internment | In 1940–1941, after this kind of census updating, the Slovak government passed laws restricting Roma movement, expelled Roma from villages, and started early internment in labor camps. |

| Legal Residency Definition | The note about “staying over 60 days” was critical: anyone who lived somewhere for less than 60 days could be expelled without due process. This was a pretext for mass expulsion or forced relocation of Roma later. |

| Census as Weapon | These small administrative notes were not harmless — they were the foundation for deportations, segregation, forced labor battalions, and even massacres later in Slovakia. |

| Local Relevance | In regions like Michalovce, Roma communities were semi-sedentary (living in marginal dwellings, outskirts of villages like Senné). They were easy to target once the government built these registries. |

Historical Context: What Happened After

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1941 | Law banning Roma movement and travel without permission in Slovakia. |

| 1942 | Roma forbidden from certain towns, forced into isolated encampments. |

| 1943–1944 | Forced labor camps established for Roma (like Dubnica nad Váhom, and later others). |

| 1944–1945 | In Slovak National Uprising chaos, many Roma were massacred by Nazi units and Hlinka Guard militias. |

This Senné listing is the bureaucratic root of that chain of events.

Conclusion

Even in small villages like Senné, the slow bureaucratic machinery of racial profiling was already at work by the end of 1939.

Today, these original census sheets — layered with their blue pencil and red pen revisions — remind us that systemic injustice often begins not with guns, but with paperwork.

History leaves traces. Some are handwritten.